Firstly, what is Trunk-Based Development (TBD)? The idea behind TBD is to have one main branch that multiple developers commit lots of smaller changes to. This main branch is the ‘trunk’ of the codebase. Developers should be committing frequently, and the main trunk should always be deployable.

Feature flags, as discussed here, are flags that allow functionality and features to be turned on and off without deployments.

Why do we need them specifically in TBD?

Decoupled deployments

Adding flags for a feature means that we can deploy the code decoupled from a release. This means we could deploy bug fixes to production, but without enabling that new feature that might still be undergoing testing.

Why do we need this? Back to that trunk, we have one main branch that should always be deployable. This is especially important when a system goes into an operations stage; we need to be able to address functionality that isn’t working as intended, but also be able to release new features.

Progressive delivery

Progressive delivery allows a feature to be rolled out, but not to everyone. Think A/B testing or canary releases: we let a subset of users see a new feature or change behind a flag. A challenge of releases is that you test as much as you can, but real end users always find something different. Be it they use it slightly differently, on a different device, etc.

Using canary or A/B lets the change be tested with real users in a real environment, but without it being available to all users at once. This way, it gets tested with a subset, and you are able to get targeted feedback. Plus, if there is an issue, you don’t affect the whole user base.

Improved rollback

When a new feature is rolled out, there is always a possibility that something goes wrong. It could be a small bug, or it could flat out not work. Without flags, the only way to roll back would be to redeploy the previous version, and depending on the deployment and hosting strategy, this could be a long process causing even more downtime.

Now, with flags, we can ‘roll back’ by just turning off the flag. The flag goes off, the feature is disabled, and the system is back operational. This is an incredibly fast way to mitigate issues, which is great for the operations piece.

The challenges

With any technique there are always challenges, and feature flags are no different.

Too many or stale flags

Creating too many flags can lead to a messy codebase and creates a constant loop of technical debt. With that, the more flags that get added, the higher the chance of stale flags—ones that are created and never used or tidied up.

To try and avoid this, clear naming conventions and lifecycle policies are important. Ensure that flags have an owner who is responsible for their lifecycle. As part of this, as the feature is completed and fully rolled out, the flag should be removed. Now, sometimes this might not be the way; depending on the feature, you might want to keep the flag to be able to turn it off in case of issues, but this should be a conscious decision.

Code complexity

Implementing feature flags is a relatively simple piece of work, especially if you use a prebuilt library or service. However, the addition of flags creates additional complexity regardless, as you have to manage the different branches of the code.

Where possible, you should use flags to encapsulate a complete feature, and avoid using them throughout the business logic. This way, the code remains as clean as possible but can still be toggled.

Testing complexity

As we said above, adding more flags creates more branches through the code—more routes that the application flow can take. This means that testing needs to become more complex to support this. We still need to be able to test the application as a whole, including the flags.

This can be mitigated by limiting the scope of flags, ideally one flag per feature. Doing so helps to limit the complexity, as there are only two states for the feature: on or off. If there are multiple flags that interact for a feature, the testing must cover each of the combinations, which can quickly grow out of hand.

Automated testing is also key to help with this; tests can be run frequently and help to check each of the possible paths without a developer needing to manually test each one.

Governance and ownership

As mentioned above, having clear ownership of flags is important. This includes the lifecycle of the flag, but also its usage.

A flag should have a clear owner to ensure that someone is responsible for it. This helps to avoid the situation where a flag gets created and then forgotten about because it’s just used and then that’s that. The owner is also responsible for checking that the flag is actually used, and if not, to remove it.

Visibility and tooling

As I’ve discussed in a previous blog, there are a number of different ways to implement feature flags. Depending on what you use, the visibility of your flags will differ.

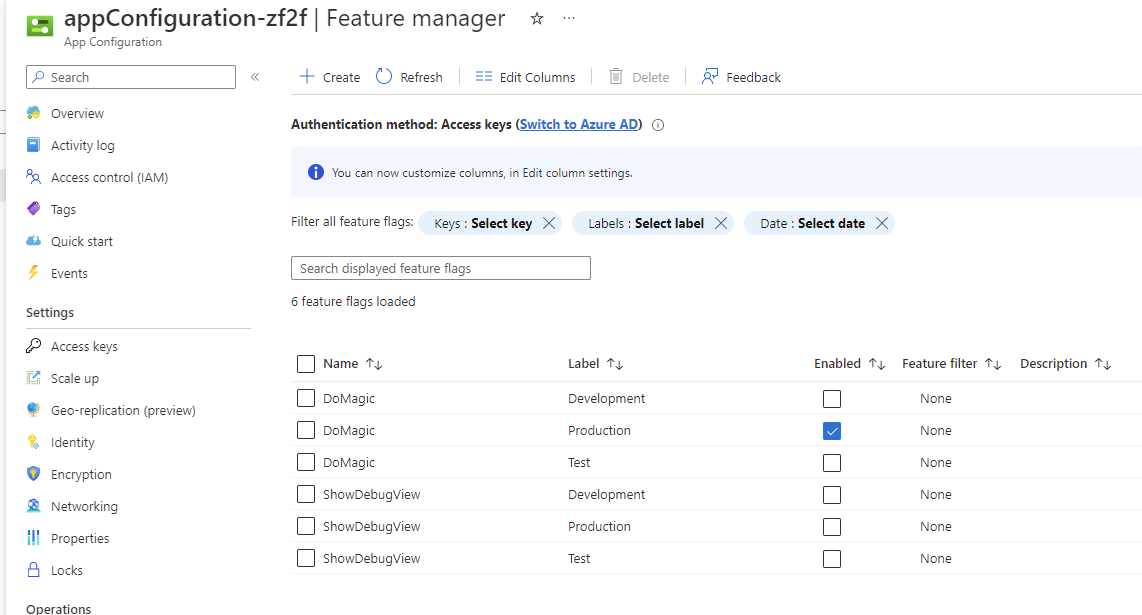

Using a feature flag service like Azure App Configuration will give you a single place to see your flags and their status.

Here you can see the flags and whether they are enabled or not, giving a quick, easy way to see what features are enabled in your application.

Here you can see the flags and whether they are enabled or not, giving a quick, easy way to see what features are enabled in your application.

As someone working in a Microsoft house, I’m always going to be biased towards App Configuration, but other services like LaunchDarkly will offer the same visibility in their own way.

However, as I have discussed before, you can implement flags just using app settings or environment variables. This is okay for quick development or small projects, but you will not have a simple, nice way to create this visibility. You would need to create your own tooling or dashboards to monitor this.

Recommended practices

There are a few things that should be considered when implementing flags, especially in a TBD environment.

- Treat flags as short-lived; they should not become a permanent piece of configuration or logic.

- Add flag management to the definition of done for a feature. Once fully complete, the flags should be cleaned up if possible.

- Implement flagging ‘properly’ using an appropriate tool, not by rolling your own in-app settings or similar.

- Automate where possible.

- Create a custom table to track flag usage, when they were created, by whom, and their current status.

- Use Application Insights or similar to track flag usage in the application; this can help identify stale flags or ones that are not being used.

Example implementation

Here’s an example of how a new feature can be implemented using trunk-based development and feature flags.

The code has been committed directly to the main branch, as expected in TBD. However, because the feature isn’t yet finished or fully tested, it’s hidden behind a flag. This allows the code to be continuously deployed without affecting end users, while ensuring the rest of the team can keep working on other features or bug fixes.

public async Task<IActionResult> Checkout(OrderModel order)

{

if (await _featureManager.IsEnabledAsync("NewCheckoutFlow"))

{

return await NewCheckoutService.Process(order);

}

return await LegacyCheckoutService.Process(order);

}In this example, the legacy checkout flow continues to operate until the team is ready to switch over to the new one. The feature can be tested safely by toggling the flag on and verifying the new path. Keeping the legacy code available means the system can quickly fall back if an issue is discovered. Once testing is complete and the business is confident in the new flow, the flag can be removed and the new implementation becomes the default.

Conclusion

Trunk-based development is a great, simple way to manage a codebase and help developers work together effectively. It does, however, introduce challenges around deployments and ensuring that other fixes or features are not blocked by one another. Properly implementing feature flags can help to mitigate this challenge and keep the code clean, safe, and decoupled from deployments.

Using both in combination should be a key part of any software development lifecycle to ensure that a team can deliver value effectively and efficiently.

I’ve seen feature flags thrown in at the last minute before to get something released while hiding another problem. Did it work? Yes — but it also created a mess that was hard to clean up later. Designing your SDLC with feature flags in mind from the start will leave you in a far better place, without needing sticky plasters over deeper issues.